| This article originally appeared in the Pittsburgh Pulp on February 12, 2004. It is reproduced here because the original article is not currently available at pittsburghpulp.com. |

|

|

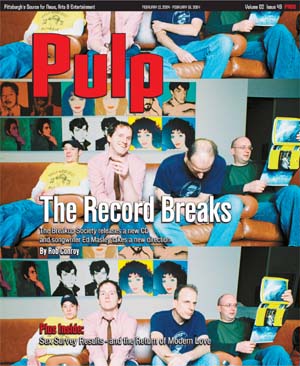

The Desperate Band Appreciation Society BY ROB CONROY

I think when people get to be my age, the tendency is to either go soft or develop a shtick," he says. "And I haven't done either. With the Breakup Society, I still rock the way I rocked when I was 20, if not harder, while addressing things from the perspective of a guy who knows he isn't even close to 20. And I almost think that this could be the niche I never had." Based upon the evidence of the Breakup Society's debut album, James at 35, he might very well be right. Although Masley is perhaps best known locally as the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette's wise-cracking rock music scribe, he has spent the better part of the past 16 years fronting such outfits as Johnny Rhythm & the Dimestore 45s, Charm School Confidential, Don Capicola and, most notably, criminally misunderstood garage-pop underdogs the Frampton Brothers. In that time, he married his long-time partner Tricia Reinhold and became a father. And he moved beyond the cleverness that marked his writing from his earliest recordings with Johnny Rhythm to emotionally ambitious songwriting that taps into the pitfalls of adult situations with humor, compassion, and musical freshness that is hard to find elsewhere. The album's opening salvo, "Robin Zander," is a case in point. In that song, Masley asks Zander, the blond vocalist for Cheap Trick who ruled covers of teen magazines in the late 1970s, to "go back in time" with him. According to Masley, "Zander" represents one man's "coming to terms with his own insignificance in the bigger picture," wrapped in the guise of a catchy, 1960s-style pop tune. "Every girl I ever had a crush on had a bigger crush on you," he sings in his distinctively yearning, somewhat reedy voice. But when mentioning Zander's name to a roomful of people 20 years after Cheap Trick's heyday elicits nothing but blank looks, he is spun into a crisis that sets the thematic framework for the rest of the album: "But if all you are's a footnote/ won't you tell me where does that leave you-know-who." The song works so well because Masley doesn't play on Zander's fallen status for cheap irony or laughs. Instead Masley gets his bewilderment across through a combination of self-deprecating humor, verbal economy and a perspective that should ring true for anyone who has ever felt like something less than an afterthought. Throughout James at 35, Masley explores the pitfalls of romantic relationships -- rare occasions in his songwriting. The album's 16 songs are infused with nostalgia and an understanding of the pathos that can lie below the surface of any relationship, a result of what Masley calls his desire to move toward Ray Davies' approach of "looking at people's lives in a nonjudgmental, empathetic way." The results are nothing short of thrilling, both musically and lyrically. "This is my big return to writing about relationships," he says. "It was this major part of my life that I never really sang about. Nonetheless, I think that it's an album of songs about girls written in the way the guy in the Frampton Brothers would have written an album of songs about girls." Interestingly enough, it's also an album of songs about girls played the way that the Frampton Brothers would have played them, as the album was recorded by Masley at former Frampton Brother (and former Pollen wunderkind) Bob Hoag's recording studio in Mesa, Arizona, with Hoag on drums and former Framptons Sean Lally on lead guitar and Ray Vasko on bass.

In fact, any further discussion of the Breakup Society -- which now features Greg "Slim" Anderson on lead guitar, Andy McDuffie on bass and vocals and Dan MacIntyre on drums -- must address the specter of the Frampton Brothers, from whose ashes the band sprang in December 2002. Over the course of 12 turbulent years and countless rhythm sections, the Framptons -- for all intents and purposes, Masley and Lally, who spent those dozen years playing Dave Davies to Masley's Ray -- gigged extensively (137 shows in 1992 alone) to little local but near-unanimous critical fanfare, and recorded three full-length albums and two mini-albums, which increased in quality and decreased in sales with each successive release. The band also met, if not surpassed, Masley's stated goal of becoming "the East Coast chapter of the Young Fresh Fellows." "I thought of that generation of bands, they were the closest anyone was coming to being the Kinks -- a fun rock-and-roll band that was capable of writing songs with a lot of heart and that had a sense of humor," he says. "They were speaking to all of the same things that Bruce Springsteen was speaking to, but it was just in a different language." Prior to meeting Lally in late 1989, Masley had been in a series of bands, starting in junior high school. Although he recalls as a kid being fond of records like Paper Lace's "The Night Chicago Died" and Bo Donaldson and the Heywoods' "Billy, Don't Be a Hero," it was watching the 1965 Beatles film Help! in seventh grade that inspired him to pick up a guitar. His parents supported his decision, he says, because they saw music as a way to keep him out of the principal's office at his Catholic school, where he could often be found, due to his "class clown" status. Eventually he began writing his own material and began recording demos with Pittsburgh journeyman Mike Michalski on bass during college. These demos became unexpected hits on local college radio, and Johnny Rhythm & the Dimestore 45s were born. An eventual addition to the lineup was Anderson, who approached Ed after an early show. "I stepped into Ed's band by sheer force of personality," says Anderson, laughing. "I pretty much convinced him that he needed me to be playing guitar for his band." After recording a regrettably produced, full-length cassette, Bud's Gun Shop, in 1989, the band called it quits, but not before Lally approached Masley in a similar fashion after a Johnny Rhythm gig. The Frampton Brothers began as an informal acoustic duo, but added a rhythm section in time to record their first record, I Am Curious (George), in 1991. The following summer, the band completed its first national tour, playing venues all the way out to Seattle, where they opened for much-admired power-pop could-have-beens the Posies in front of a 500-plus crowd and recorded with Young Fresh Fellows producer Conrad Uno at Egg Studios. Both Masley and Lally remember the Posies show as a highlight of their Frampton Brothers experience. "We felt nothing but wide-eyed optimism at that point," Lally says. Masley looks back fondly, but for different reasons. "At the Posies show, I got the mic knocked into my face and was bleeding -- that was a real highlight," he says. "I mean, we played to a roomful of people in the 'cool' city and they worshipped us. Looking back, they probably would have given the same response to anyone." Although George found the band taking a decidedly jangly direction, prominently featuring Lally's Rickenbacker 12-string, its live shows and subsequent releases -- 1993's Don't Fall Asleep, Horrible Things Will Happen, 1994's Hate You e.p. and 1996's cassette-only The Frampton Brothers Play the Hits of the Staten Island Ferries -- found the sharpness of both their musical and lyrical attack increasing. Although the music was still power pop, the band began adopting a more crunchy, garage-band sound, thanks primarily to Lally's purchase of a Les Paul Standard, which helped to unleash his heretofore untapped ability to wrench the perfect note from any spot on the fretboard with real feeling and panache. At that time, Masley's voice may have been a bit rubbery around the edges, but he has always been his own best interpreter. Listening to those records now, it's hard to imagine anyone but Masley convincingly navigating his own private lyrical tightrope of honesty and irony. When Nirvana broke at the end of 1991, it looked like things might be opening up for outfits like the Framptons. Despite the band's obvious talent, however, Masley had reservations about the likelihood of any such national success. "Pop songs that were sung by guys with weird voices and were played too fast and sloppy were suddenly all over the radio," Masley says, "and that certainly seemed like it might bode well for us. I think that I was pretty realistic about it, though -- I knew we'd have to leave Pittsburgh and I knew Lally wouldn't do it and Trish didn't seem excited about doing it. At that point, I just thought that this is what I do, not how I put a roof over my head. Although I had delusions of a lucky break, I knew we didn't have the commitment. I didn't want to be on the road 200-some days a year." Tensions within the band began to increase, compounded by disastrous tours, low-selling but highly regarded releases, ill-attended local shows and volatile lineup shifts that culminated in an uncharacteristically well attended breakup show in March 1997 at Luciano's, a coffee shop and occasional music venue which stood across Forbes Avenue from the Duquesne campus. Oddly enough, according to Masley, the breakup was therapeutic. "With everything out in the open, it kind of made it possible for Lally and I to talk again, which we hadn't really done in four years or something," he says. "So we started getting together and writing songs about the breakup and the band in general, self-demythologizing songs, and it just felt really good." In the summer of 1998, Masley and Lally decided to recruit Vasko, who had served as the Frampton Brothers' bassist for the better part of two years prior to the breakup, and Hoag, who had last drummed for the Framptons on a regular basis in 1994, to record another album at Egg Studios. The resulting album became the final Frampton Brothers release, 1999's File Under F (For Failure), which featured such latter-day Framptons classics as "Dressing Room" -- a mordantly tongue-in-cheek, real-life account of being ousted from club-gig headliner Velvet Crush's dressing room in Albany, New York -- and the self-lacerating title track. "When we listened to the mixes for that album, I think that was probably the high point in Frampton Brothers history emotionally," Masley says. "We all felt that we had somehow just done the greatest thing we'd ever done and it was this brilliant conclusion to the whole ridiculous saga. The problem quickly became that when we found a label to put it out, it was increasingly obvious that we would have to be a band again to promote the record -- that we couldn't just be goofballs who went in and recorded this record. We'd have to actually play." With that, Dan MacIntyre joined as the drummer and the band enjoyed a second wind of sorts, being the only Pittsburgh band selected to play two NXNW Festivals and the first to play the SXSW Festival. By all accounts, however, the band was unraveling rapidly. In December 2000, MacIntyre quit. Then, just after the remaining three recorded the basic tracks for what became James at 35 with Hoag during the summer of 2001, Vasko left the band. According to Masley, "The band had become a touring production of Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf that had stopped touring." After a lurching final show at the Quiet Storm in the summer of 2002, Vasko's replacement, Joe Dello Stritto, quit, and the rest of the band amicably decided to call it a day. Nearly two years after the breakup, Lally says that he does not think the band could have hoped for more success. "We never stood a chance -- we weren't goofy enough for the late '80s, RAWK enough for the early '90s, coherent enough for the late '90s and optimistic enough for anything later," he says. Unlike prior albums that Masley released with the Frampton Brothers, which contained songs written as far as six or seven years apart from one another, all but one of the songs on James at 35 were written within a relatively brief period of time. Additionally, after Masley composed "Robin Zander" and "The Summer of Joycelynn May" -- which follows "Zander" both thematically and literally and finds Masley contemplating his first real-life, preteen crush from an adult perspective -- the romantic song cycle began to take shape. "As soon as I wrote 'The Summer of Joycelynn May,' it occurred to me to do the songs in this kind of cycle, because 'Joycelynn May' picked up musically and lyrically from where 'Robin Zander' left off," he says. "That's when it occurred to me to write it as an album. I think the album as a whole is somewhat of a departure [from Frampton Brothers albums] because it's a more focused collection of songs." At that point, Masley says, the "arc of the story took over and I just pulled what I could from my pre-Trish experiences" to shape the album. He repeatedly stresses that, while the emotional content of the album is based upon some of his early romantic experiences, he did not include any material that reflected his current relationship with his wife. "I never understood the idea of writing songs specifically about the problems you're having in a relationship with someone that you're professing in the song to be so important to you that you would write a song about it," he says, "because you're selling them out and it's clear that you're so self-involved that your art matters more to you than the person who loves you." Besides, he adds, happy marriages with great kids aren't effective subjects for great albums. Not that he feels that anger is the secret to great art. "I think that some artists are at their best when they're angry, but I don't think I'm one of those artists," he says. "I think that I do 'hurt' better than 'angry.'" Since the basic tracks for James at 35 were recorded in the summer of 2001 with the same lineup featured on File Under F, the Breakup Society's basic sound is not always markedly different from Frampton Brothers albums. However, according to Masley, much of the credit for the finished James at 35 rests with Hoag, who sang backing vocals, played drums and keyboards, recorded, engineered and produced the album. A close listen to the record supports Masley's analysis, as all sorts of creamy harmonies, previously uncharted keyboard sounds and exotic percussion spring from the speakers with psychedelic ease, lending the record a feel that is completely distinct from Masley's prior releases. Not bad for a man who lives across the continent in Arizona and who has not been an official member of the band for 10 years. "The eight 16-hour days that Bob and I spent in the studio in late 2002 doing all of the vocal tracks and instrumental overdubs was the greatest musical experience of my entire life," Masley says. "This totally focused, album-making atmosphere was everything I thought being in a band was going to be but never panned out to be...and it sounded good." Armed with the knowledge that he'd just completed the record of his life, Masley immediately began seeking bandmates to help him promote it. He had been discussing beginning a project with Anderson before the demise of the Framptons and proceeded accordingly upon his return from Phoenix. His next step was to give MacIntyre a call. "Dan is into power-pop and garage-rock and has always really liked my songs and has been a very supportive presence in the band," he says, having worked with MacIntyre in Charm School Confidential as well as the Framptons. "I really enjoy being with my daughter, so if I'm going to leave her to do something else, it better be fulfilling and exhilarating and fun. I knew that Dan would help to foster that environment." A chance meeting on the street with bassist McDuffie, whom Masley knew from his work in Kill Bossa, completed the original quartet. Masley liked what Hoag's keyboard tracks added to the record, so he wanted to get someone to play them live. Rich Rust, a friend from the early 1990s who played in local bands including the Nixon Clocks and the Affordable Floors, e-mailed him after moving back from California. Based upon a shared love for Steve Nieve of the Attractions, Rust was recruited last May. "At first, he'd show up and he'd be really quiet...but after a couple of months, he was suddenly the loudest person in the room," Masley says. "And he'd truly become an essential part of our band -- exactly what I had in mind. I think that the show we played at Rosebud on Halloween was probably the best show I've ever played, and the parts that he had written for the songs were what brought it to this whole other level. He had made keyboards part of our sound, which is something that I'd never anticipated." Right around Thanksgiving, Rust started missing practices. Masley thought he was losing interest in the band, but it was more serious than that. "It never, ever, ever occurred to me that he was really, really sick. He came to the rehearsal right before the AC/DC tribute that we played in December and he just looked sick as hell. Then he played the show at the Pub and he was leaning against the wall, hunched over the pinball machine while waiting to play, then he got up and played his set and went out the side door." On Christmas Eve, Rust was diagnosed with cancer and began receiving chemotherapy the next week. By January 13, exactly one month after the 31st Street Pub show, Rust was dead. Masley is still visibly shaken as he talks about it. "I had never seen death move in on someone like that," he says. "He was being his total goofball self on Halloween, and he was fine at Laga on November 22. Maybe he was sick already, but he didn't seem it." Masley is unsure whether Rust will need to be replaced in the band, but he is firmly aware of the gravity of the situation outside the band's parameters. "It was a great tragedy for his family," he says. "Us having to play as a guitar band seems pretty much like the smallest problem in the world compared to that. It all sucks on so many unfathomable levels for so many people." The band felt that their first show without Rust, on January 30, went as well as could be expected. "What Rich brought to the band was a great sense of fun, and his death is a great loss," Anderson admits. "However, everybody's gotten along well in this band and the atmosphere in our working relationship is better than any project I've been in. I really, really look forward to rehearsals and wish we could get together more often than we do. That's saying something." The fact that the material is of such a high quality doesn't hurt, Anderson says. "Although I've always been a huge fan of Ed's writing, he's always improved over time. Unlike most artists, who do most of their best work in their 20s, Ed is doing his best work in his 30s, and barring any unforeseen extreme success, I expect it to continue. It seems that success after a certain time tends to dilute art, so in some ways it's good that Ed hasn't had a ton of commercial recognition." To Gregg Kostelich, president of Get Hip, the garage-rock label and distribution center that is releasing James at 35, the autobiographical ambiguity of the album's subject matter is one of the keys to its appeal. "The fact that we don't know if it's autobiographical or just musical -- right there, he wins as an artist," he says, noting that the heartbreaker "She's Using Words Like Hurt Again" is his favorite song on the album. "This album is a really good piece of work. If the record gives you goosebumps, then it's a hit -- it doesn't matter what the commercial rewards are. And several songs on this album did that to me." Scott Mervis, who has been Masley's Weekend editor at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette since 1996 and who has known and edited him since 1988, says that part of the key to the album's success is Masley's ability to connect with the preadolescent version of himself pictured on the album cover. "He is still that person in the picture on the album cover," Mervis says. "He is still in touch with the childhood version of himself." With or without access to his inner child, Masley is characteristically reflective when it comes to his prospects for success. "To be successful, I'd have to do things that were distasteful to me," he says, "so I'm looking for a different kind of success: putting out records that I admire, that we can do our best to get into the hands of other people who might admire them, and take it from there. "I keep it real, as they say in parochial school. And that's not terribly exciting from a marketing perspective if you're not out waving guns around or beating hookers. I don't have a rock persona I adopt. I don't get into melodrama. I just write about the things that I think shape the way we see the world and how we fit into that world, with a sense of humor and, I'd like to think, a sense of self-awareness. And that's not for everyone. Some people want a superhero on the mic, but I'm more Peter Parker. And I like that." Let's hope he doesn't don a Spiderman costume anytime soon. Long live the three-button suit and Les Paul.

|